Most adults agree that explaining death to children is one of the toughest conversations we can have. And one of the biggest mistakes we often make is not talking about death with kids.

Research shows that most children experience the loss of someone they love by the time they finish high school. Nine in 10 children will grieve the loss of a family member or close friend. One in 20 will lose a parent. Children’s losses are diverse, from losing a grandparent from Alzheimer’s disease to losing a parent from cancer or a classmate from a school shooting.

Children are acutely aware of the emotional life of their families and friends and need special attention to help them grieve. It is important to consider their age and developmental level. This article is about ways of explaining death to children and how to help them cope with the death of someone close. It is for parents, of course, but educators often are also on the front lines when tragedy strikes.

At What Age Does a Child Understand Death?

Most children don’t fully accept the fact that death is irreversible until they are around 10, though by age 5 or 6 they will concede that death is inevitable.

For me, these facts took on new meaning after doctors diagnosed my 47-year-old son-in-law, Don, with terminal brain cancer. When it came time to tell the children, we felt at a loss about what to say.

Lily, age 10, and Emmy, age 6, are my daughter’s children with Don. Kaiya, 2, and Lukas, 4, are my son’s children. The four of them are very close and live near each other.

Despite my 50 years as a developmental psychologist, I had not one clue how to begin explaining death to children. Neither did my daughter, Alexis. We asked psychotherapists we knew, conferred with social workers, and searched the internet. We asked advice from colleagues and friends.

The social workers and nurses told us to be “transparent,” without telling them too much or too little, and not too early, or too late. We felt like Goldilocks without a clear way to know what was “just right.” As the end came near, everyone seemed certain we should tell them that Don would die soon, making sure we used the word “die,” but no one seemed to know how to compose the rest of the sentence.

Children of Different Ages Respond to Death Differently

Developmentally, children grieve differently and have differing conversational needs. What is essential at any age is for children to feel the loving presence of an adult who accepts their reactions, thoughts, and feelings, no matter what their experiences.

Lukas, like all babies, reflected the stress around him. Usually, a happy, easy baby, he began having trouble sleeping and seemed especially attuned to his sister’s distress. We focused on keeping his routine steady and providing security and support through our physical presence with him. For infants and small children, comfort and consistency are crucial.

For Kaiya, Lukas’ four-year-old sister, simple explanations like “Uncle Don’s body has stopped working and the doctors can’t help anymore,” seemed to be the key. We were also careful to say that he was dying of cancer, so that she wouldn’t be alarmed when someone caught the flu.

We quickly learned that explaining death to children is challenging and doesn’t always result in lengthy conversation.

Six-year-old Emmy refused to talk about the situation. If you told her you wanted to talk about what was happening to Daddy, she would change the subject, or laugh and walk away. A conversation with her might look like this:

“Are you okay?”

“No.”

“Do you want to talk about it?”

“No.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

We tried many times to tell Emmy, but she could not tolerate the idea that Daddy was dying. Young children often deny facts that upset them, and that’s okay. You cannot force them to listen. When he died, however, she was the most upset.

“Now, I’ll never have a daddy,” she said.

She wanted to see her daddy after he died, so we allowed her to do this. She seemed okay for a while. A month later, though, she began having rages over small things, banging her head and tearing her hair out, kicking and screaming. We took her to a therapist who helped us discover that she felt Don’s death was her fault. This is very common among school-aged children.

Emmy also told the therapist that she thought she made a mistake asking to see her daddy’s body. Children her age often display magical thinking under stress, and she may have been thinking she could bring him back, or that he wasn’t really dead. With the start of school and the resumption of her participation in activities like Taekwondo and volleyball, she seemed to be coping better.

Lily, the ten year old, spent little time with her dying dad, but she was ready to talk about it well before it happened. We realized this when we noticed her sneaking around to hear hushed discussion in the “other room,” where people went to exclude her. We asked her what she thought was going on.

“He’s really sick,” she said. “He might die in like five years.”

“He doesn’t really have that long.”

“Three years?”

“No.”

“One?”

“No.” She began to cry.

Don died at home a week later. Lily was still sleeping when we went to tell her that he had died earlier that morning. It was too hard for Alexis, so I mustered up my courage and said “Honey, Daddy died this morning.”

“Okay,” she said, simple as that.

“Do you want to see him?”

“No,” she said.

“Okay. Do you want to go to Starbuck’s while the people come to get him?”

“Yes. Can I have caffeine and sugar?”

“Yes.”

On the way to Starbuck’s, Lily asked for permission to feel relieved. Don had been horribly sick for a year.

“Is it okay to be happy?”

“Of course, I said. “It’s okay to be any way you feel. In the next few months, you’ll feel up and down, sad and angry, relieved it’s over, and happy you’re alive. It comes in waves, and all of it is okay.”

Children are Resilient

Whenever we contemplate the task of explaining death to children, we must also recognize that children are resilient. The research shows that the death of a parent does not have to have long-term, negative consequences. In fact, the grieving process can be healing when children feel an important part of the process.

In her article about helping children find meaning from the loss of a loved one, Dr. Marilyn Price-Mitchell emphasizes that memories can be a rich source of strength and courage for children, rather than an anchor to their sorrow.

It is important to help children keep a routine. Keep them in the same school, in the same home, and, if possible, with the same friends. Make sure you don’t get so wound up in your own grief that you can’t be responsive and present to children’s needs. Words count, but your loving attention is the key.

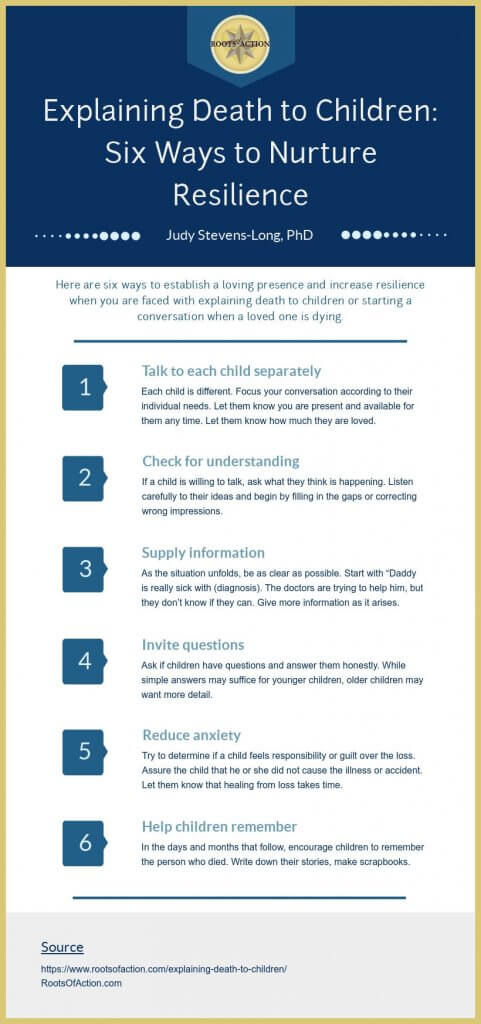

Explaining Death to Children: Six Ways to Nurture Resilience

After much research, discussion, trial, and error, here are six ways to establish loving presence and increase resilience when you are faced with explaining death to children or starting a conversation when a loved one is dying.

1. Talk to each child separately.

Each child is different. Focus your conversation according to their individual needs. Let them know you are present and available for them any time. Let them know how much they are loved.

2. Check for understanding.

If a child is willing to talk, ask what they think is happening. Listen carefully to their ideas and begin by filling in the gaps or correcting wrong impressions.

3. Supply information.

As the situation unfolds, be as clear as possible. Start with “Daddy is really sick with (diagnosis). The doctors are trying to help him, but they don’t know if they can. Later, you might say, “The doctors are saying that Daddy isn’t going to get better.” Finally, if they will listen, you can say, “Daddy isn’t doing well, and the doctors say he will die soon.”

4. Invite questions.

Ask if children have questions and answer them honestly. While simple answers may suffice for younger children, older children may want more detail.

5. Reduce anxiety.

Try to determine if a child feels responsibility or guilt over the loss. Assure the child that he or she did not cause an illness or accident, that they cannot cure or bring the loved one back. Let them know that healing from loss takes time.

6. Help children remember.

Explaining death to children is the first step in a long process of grieving and remembering. In the days and months that follow, encourage children to remember the person who died. Write down their stories, look at photos, draw pictures, make scrapbooks. Recalling happy memories helps children heal.

Infographic to Use and Share

The following infographic was created from the content of this article. Please feel free to use and share it with whomever you think may benefit from these six simple ways to nurture a child’s resilience when a loved one is dying or has died.

Editor’s Note

Editor’s Note

Dr. Judy Stevens-Long’s new book, Living Well, Dying Well, is an easy-to-read and practical guide to the issues related to illness, aging, and dying. It’s a book that should be read by anyone who wants to understand the positive choices that are possible in the final phases of our lives and how to create joy and comfort until the very last moment of life.

Also see Dr. Stevens-Long article, More Talking to Children about Death, where she discusses how a child’s sense of identity is changed by the death of a parent and pointers for helping kids through those difficult first years.

Published: December 28, 2018