Terrorism has become a sad and terrifying part of life in the 21st century. It is difficult enough for adults to understand and make sense of violent acts perpetrated against innocent people, but what about children? How do adults help kids make sense of terrorism while promoting children’s well-being at the same time?

As the recent act of terrorism in London played out on live television, children and adults struggled with similar questions: Why did this happen? Could it happen to us? Should we be afraid?

Often, our first reaction is to protect children from frightening news. With very young children who are not directly affected by terrorism, this approach is most preferable. But if your children are school-age, the news of terrorism spreads quickly in today’s world.

Harold S. Koplewicz, M.D., president of the Child Mind Institute says parents should help children express feelings, provide comfort, and engage in dialogue that helps kids feel safer. When there is wide news coverage of an act of terrorism, Koplewicz encourages parents to break the news to children themselves rather than waiting for children to hear it from another child or TV broadcast. His wise advice includes the following: 1) Take cues from your child, 2) Remain calm, 3) Reassure your child that he is safe, 4) Help her express feelings, 5) Be developmentally appropriate, and 6) Find ways to memorialize those who have been lost.

When we answer children’s questions about “why” with answers like “terrorists are monsters and very bad people,” we heighten their anxiety and fear. This is exactly what terrorists hope to achieve. Even in times of unspeakable horror, rather than focusing on the perpetrators, parents can evoke the power of compassion and empathy for the victims, and highlight the kindness of ordinary people and emergency responders who are so willing to help.

Children should understand that there are violent people in the world who use fear as a weapon. They are a small minority of people and the chances of being affected by acts of terrorism are minimal. Most people in the world don’t wish to harm other people. This kind of conversation between parents and children helps kids feel safer and gives them a sense of risk proportion.

At the same time that we want children to feel secure, we also want them to understand that fear, loss, and grief are natural parts of life. When parents help children feel the pain of tragedy and loss, they increase a child’s empathy, resilience, and self-awareness. To support children through grief, see Loss of a Loved One: Finding Meaning through Metaphor. When we find ways to remember and honor those who have died—whether from acts of terrorism or natural causes—we contribute to our own and others’ healing.

Tackling Moral Dilemmas with Children

Making sense of acts of terrorism is a complex moral dilemma. For children who have reached middle and high school age, it can be an opportunity to help them understand the deep values that unite civilized society like justice, freedom, and integrity.

Because they are just developing their ability to morally reason, children get most confused when they watch adults (and nations) respond to terrorism. What is the difference between justice and revenge? When children see bombs being dropped on terrorist targets, they can internalize that to mean, “When someone harms me or my family, it is okay to hurt them back.”

Adults can help children understand justice and retribution by talking about the values behind these two concepts. There are sticky issues here—and sometimes there are no concrete answers! Getting kids to reflect on and discuss moral dilemmas like terrorism is important to their development as human beings.

Justice, Retribution, and Terrorism

Justice is understood differently by different cultures, depending upon their history. At the core of justice are certain shared values about moral rightness, fairness, and ethics that if breached call for punishment. Justice is an integral part of the American legal system, a foundation of how our culture thinks about crime and punishment. Justice is about how our actions have consequences.

John Stuart Mill, a British philosopher, suggested that justice evolved from two natural human tendencies: retaliation and empathy. Humans have a natural empathy for people who are hurt. Indeed, the human loss from acts of terrorism can be overwhelming to everyone, not just those who lost loved ones. Through our ability to put ourselves into another person’s place, we feel a natural desire to retaliate against those who hurt us. Thus, Mill believed the laws of justice evolved from the dichotomy between empathy and retaliation.

What is the difference between justice and revenge? Justice is undertaken and supported by legitimate judicial systems founded on certain ethics and morals. It is meant to be restorative. On the other hand, revenge is often done to make others suffer the same or greater pain than that which was originally inflicted. It can be argued that the type of killing done by groups associated with terrorism, like ISIS and Al Qaeda, is steeped in revenge because it is designed to inflict the greatest harm on innocent people.

Michael Sandel, a Harvard law professor, explores the meaning of justice in his book Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do? He delves into the moral source of justice and the virtues that justice seeks to honor. He says we can’t determine who deserves to be punished until we understand the virtues behind our actions. In other words, how do we bring meaning to justice?

Helping children understand the meaning of justice and its underlying values is important. Why? It develops a child’s ability to develop skills in moral reasoning. And it helps them distinguish between concepts such as justice, retaliation, and revenge. When they are faced with their own moral dilemmas, they will be better able to respond.

Here are a few ideas for teachers and parents that can help middle- and high-school-age children better process their feelings after terrorism attacks and understand the distinctions between justice and revenge.

Classroom Activity

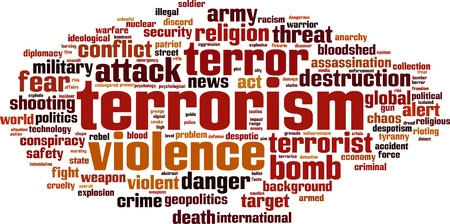

Ask students to describe their reactions to the London terrorism attack in one word. For classrooms, this can be a great activity to begin discussing terrorism and the moral dilemmas associated with it. Teachers might ask each child to write a word that describes the attacks or the feelings they associate with the attacks on a sheet of paper. When the papers are collected, the teacher or a team of students (depending on age) can sort the words into piles and manually create a word cloud on the board. Or, a word cloud generator such as Wordle can be used to create a computer model similar to this one:

Once the words are visually displayed in the classroom, it’s time to dig deeper into meaning. Why do we feel the way we do? What are the values behind our feelings? The teacher facilitates dialog to help children understand the important concepts of justice, empathy, retribution, revenge—and a host of other values that may emerge.

Family Dinner Table Conversation

An event like the London attack is different for each family. Talk to your children about your feelings. Ask them about theirs. They are likely too young to remember the day when the World Trade Center was attacked and the immense grief you felt. Tell them about that day. Talk about justice—and the consequences of our actions. Share your own moral dilemmas and how you worked through them, or still struggle to understand.

Current events present an opportunity to talk about national values. It is also an occasion to talk about family values. How do your kids experience the consequences of their actions when they are dishonest, selfish, or treat others with disrespect? Families should initiate conversations about values and moral dilemmas often in a child’s life.

Families who create open environments for dialogue with children around values and meaning in life nurture kids who grow up to reason for themselves. Through respectful listening and conversations about the moral dilemmas of our day, including terrorism, you can help your child develop into a caring, compassionate, and engaged adult.

©2011, 2015 Marilyn Price-Mitchell

Image Credit: Bianca Dagheti

Published: November 16, 2015

Tags: moral development, positive values